It’s in words that the magic is—Abracadabra, Open Sesame, and the rest—but the magic words in one story aren’t magical in the next. The real magic is to understand which words work, and when, and for what; the trick is to learn the trick.

- John Barth, Chimera

It’s been quite some time since Hooks were officially stabilized in React 16.8, and with them came a fundamentally different way of understanding the way our applications work. This is both a blessing and a curse: Hooks are much closer to the React programming model and help avoid a certain class of subtle and confusing bugs, but some developers have also expressed concerns that React is becoming a black box. These concerns are completely valid; Hooks can often seem "magical," since most of the complexities are hidden away in React's internals.

Much of that "magical" feeling is simply due to the fact that Hooks are based on some prior art and programming language research that many developers simply aren't familiar with. Understanding some of the motivations and inspirations for Hooks can help build a mental model for what's happening behind the scenes. While there are several sources of influence on the original Hooks proposal, arguably the most important is the notion of algebraic effects.

❗❗ Note that this article is not an introduction into how to use Hooks or how Hooks work internally. This is merely a way to think about Hooks. For more information about how to use them, I suggest starting with the docs.

Before diving into the details of algebraic effects, let's first take a step back.

Why Do We Need Hooks?

Class components seemed to be working well enough, why add another way of writing components that, at least at face value, do the same thing?

One of React's core principles is the idea that an application's user interface is a pure function of that application's state. Here, "state" can refer to any combination of local component state and global state, such as a Redux store. When that state changes and propagates through your component tree, the output represents your new UI after that state change. This is, of course, an abstraction over the nuts and bolts of how that update actually happens, since React handles the actual reconciliation and DOM updates that are necessary, but this core principle means, at least in theory, that our UI is always synchronized with our data.

Of course, this isn't always true. Class components expose certain scenarios that allow us to ignore changes in state if we don't effectively handle those state changes in our lifecycle methods. Dan Abramov wrote an excellent article on some common pitfalls related to this that's worth a read for more detail. In short, class components use different lifecycle methods to handle side effects, but that maps side effects to DOM operations, not state changes. This means that while the visual elements of our UI may respond to state changes, our side effects might not.

Because class components have to do these internal updates to synchronize their internal state when props change, they are by definition impure. But wait, you say, I thought we said that UI was a pure function of state.

Precisely. This is where Hooks come into play.

Hooks represent a different way of thinking about effects.

Instead of thinking about the entire lifecycle of a component, Hooks allow us to narrow our focus to only the current state.

We can then declare the states in which we want our effects to run, ensuring that those state changes are reflected in our effects.

Of course, an "effect" can be many things, from handling state with useState, making network requests or manually updating the DOM with useEffect, or calculating expensive callback functions with useCallback.

But how do we reason about those side effects within a pure function? I'm glad you asked!

An Introduction to Algebraic Effects

Algebraic effects are a generalized approach to reasoning about computational effects in pure contexts by defining an effect, a set of operations, and an effect handler, which is responsible for handling the semantics of how to implement effects.1

Algebraic effects generalize over a whole host of potential uses, like input and output, handling state, async/await, and many more.

This is a little abstract, so let's write some code to see how this works in practice. Unfortunately, JavaScript doesn't actually support algebraic effects, although React might mimic them internally. While there are a few different languages2 that support algebraic effects, we're going to use Eff, a functional programming language designed specifically around algebraic effects. Don't worry, most people won't know Eff, so I'll explain some syntax as we go along3.

A common use case for algebraic effects is handling stateful computations.

Remember that effects are just in an interface with a set of operations.

In Eff, we defined effects with the effect keyword and a type signature:

(* state.eff *)

(* A user with a name and age *)

type user = string * int

effect Get: user

effect Set: user -> unit

Once we've defined what effects our effects will look like, we can define how our effects are handled by using the handler keyword.

let state = handler

| y -> fun currentState -> (y, currentState)

| effect Get k -> (fun currentState -> (continue k currentState) currentState)

| effect (Set newState) k -> (fun _ -> (continue k ()) newState)

;;

Hmm, this looks a little trickier -- let's break it down a bit.

We have a handler with three branches, and all of them return a function.

That function will be used to handle some effect (or lack thereof).

The first branch, y -> fun currentState -> (y, currentState), represents no effect, which happens when we reach the end of the block we're handling (which we'll see shortly). y here is the return value of the function, so this simply returns a tuple of the inner return and the state.

The second and third branches match our effects, but there's a suspicious argument k.

k here is a continuation, which represents the rest of the computation after where we perform an effect.

Aside: GOTO, but better

At my heart, I am something like the goto instruction; my creation sets the label, and my methods do the jump. However, this is a really powerful kind of goto instruction. If your hair is turning green at this point, don’t worry as you will probably only deal with users of continuations, rather than with the concept itself.

This little gem comes from the GNU Smalltalk Continuation documentation.

For some of you, the reference to GOTO might make you a little nauseated, but there's a reason that continuations still have their place as a control flow, which is about context.

One of the more treacherous aspects of GOTO is getting plopped into an invalid context, but with continuations, you're really storing an in-flight process, so the variables, pointers, and so on will all be valid.5

Because continuations represent the entire process in action, they're essentially a snapshot of the call stack at the time of the effect.

When we get to an effect, it's almost as if we hit a giant pause button on the computation until we properly handle the effect.

Calling continue k4 is like hitting the play button again.

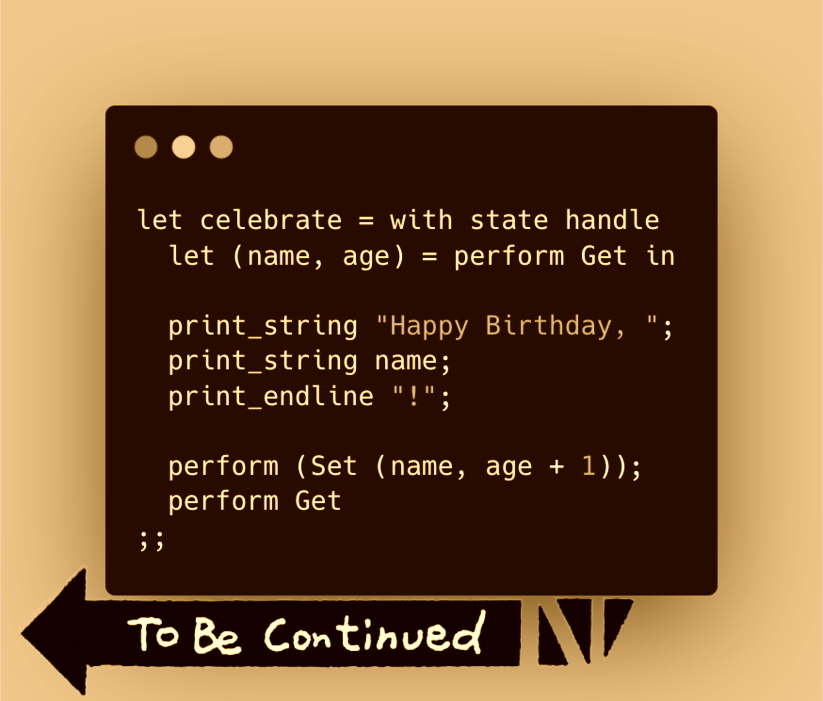

Alright, I think we're ready to see our effect handlers in action. Right now, we have a user in state; let's wish them well on their birthday:

let celebrate = with state handle

let (name, age) = perform Get in

print_string "Happy Birthday, ";

print_string name;

print_endline "!";

perform (Set (name, age+1));

perform Get

;;

celebrate(("Henry", 39));;

When we start off this computation, we first Get our user from state, which runs the second branch in our handler.

At this point, we've hit the pause button, so the function has stopped running while we get this from state.

The handler gives us back a function, which calls continue k currentState, resuming our computation with the value of currentState.

This same flow happens every time we perform an effect.

Hit pause, do some work, hit play.

And here, dear reader, is where the power of algebraic effects really shines.

You see, it doesn't really matter how we hold state.

Sure, right now it's just an object in memory, but what if it was in a database?

What if it was stored in a browser's localStorage?

As far as celebrate knows, these are all the same.

If we wanted, we could swap out our state handler with a redisState handler that stored state in a key-value store.

In JavaScript, your code has to be aware of what's synchronous and what's not. If this were to change in the future, and state was handled asynchronously, we would need to start handling Promises, which would require changes across everything that touches this function. But with algebraic effects, instead of maintaining a running process that holds a reference to a different process, we can simply stop the current process altogether until our effects are finished.

Of course, state isn't the only thing that we can handle with algebraic effects.

Let's say we have some network request we want to make or cleanup we want to execute, but we only want to do it after our function is done.

We'll call it a Defer effect.

effect Defer: (unit -> unit) -> unit

let defer = handler

| y -> fun () -> ()

| effect (Defer effectFunc) k ->

(fun () ->

continue k ();

effectFunc ()

)

;;

Notice that continue k () doesn't have to be the last part of the handler, as it was in our state handler.

We can call continuations whenever we want and however many times we want -- remember, they're just representations of a process.

To make sure this works as intended, let's make a quick sketch of how this might work in practice:

let runWithCleanup = with defer handle

print_endline "Starting our computation";

perform (Defer fun () -> print_endline "Running cleanup");

(* Do some work *)

print_endline "Finishing computation"

;;

runWithCleanup();;

When we run this, we get the following in our terminal:

$ eff defer.eff

Starting our computation

Finishing computation

Running cleanup

Great! As expected, our cleanup function ran after the continuation.

At this point, I'm sure you're thinking "Great, so we can sort of pause execution whenever we want. What does this have to do with Hooks?"

Well, the two effects that we laid out here in Eff exist in React, just by other names: the state handler (unsurprisingly) mirrors useState, and our defer handler works a lot like a simplified useEffect.

The examples from before aren't directly related to user interfaces, but the mental model of pausing and resuming processes, as well as scheduling effects after continuations, are core to understanding Hooks and the future of React.

Algebraic Effects in React

So let's turn our attention back to React.

Previously we discussed why we need Hooks, but the question arose of how we think about Hooks.

Recall our original definition of algebraic effects as a set of operations and a set of effect handlers.

The operations here are our Hooks (i.e. useState, useEffect, and so on), and React handles these effects during a render.

We know the effect handlers are a part of the React render cycle because of some of the rules of Hooks.

If, for example, you attempt to call useEffect outside of a React component, you'll likely get an error along the lines of Invalid hook call. Hooks can only be called inside of the body of a function component.

Similarly, if you perform an effect in Eff without properly handling it, you'll see Runtime error: uncaught effect Defer.

While we had to set up the handlers ourselves in Eff, in React they're set up as part of the render cycle.

So why does this matter?

Understanding that React is responsible for much of the implementation of when and how your effects run is important because it allows us to stash enormous amounts of complexity within React.

For example, one of the key uses of useEffect is as a scheduler.

Particularly for computationally expensive UIs (such as complex animations), scheduling units of work is incredibly complex, and React needs to be able to make decisions about what work is the highest priority.

At a higher level, React can pause and resume the rendering of individual components, which again can prioritize onscreen components or components that respond to user input.

Andrew Clark wrote an excellent overview of how React Fiber works and its design goals, but this tidbit about scheduling is particularly important here:

A push-based approach requires the app (you, the programmer) to decide how to schedule work. A pull-based approach allows the framework (React) to be smart and make those decisions for you.

By allowing React to separate effects and rendering, we allow it to relieve us of some complexity. This will become increasingly important as React moves more and more towards features like Suspense and Concurrent Mode.

Conclusion

Often the most painful bugs come from when our mental model of a tool doesn't quite line up with how it works.

For many React developers, I think we struggle to see grok what's happening when we call useState.

My hope is that understanding algebraic effects at least provides a slightly better model for what Hooks are doing behind the scenes.

Of course, it's worth reiterating that this is not to suggest that this is how Hooks actually work -- it's simply to try and make sense out of them.

This article didn't dive too much on the literal inner workings of React, but hopefully it instead provided a better intuition about Hooks and effects more generally. Algebraic effects are a fairly recent area of programming language research, and I know for myself at least, it took a lot of reading to better understand what they are. If you want to do a deep-dive into the research behind algebraic effects, I've put some suggested reading below.

Despite some complaints in the community about React becoming a black box, it's important to remember that new tools exist for a reason, and that a primary goal of Hooks and React more broadly is to shield us from a certain amount of complexity that we don't want to deal with, allowing us to focus on building better UIs and delighting our users.

Suggested Reading

- Daan Leijen's talk "Asynchrony with Algebraic Effects" gives a great overview of how algebraic effects generalize to even more use cases like iterators,

async/await, and more. If reading papers is more your thing, he also wrote "Algebraic Effects for Functional Programming", which lays out some of the specifics. Daan is the creator of Koka, another research language focused on algebraic effects. - Matija Pretnar (the creator of Eff) has an excellent tutorial paper on algebraic effects.

- If you want to see how algebraic effects work in another language, you can find a tutorial here on algebraic effects in Multicore OCaml. There's also this talk by Leo White on the implementation of an effect system in OCaml.

- For an overview on React Fiber, algebraic effects, scheduling, and the future of React, Brandon Dail gave a talk a few years ago called "Algebraic effects, Fibers, Coroutines Oh my!" on how algebraic effects are implemented in React.

1 This separation between an effect and its handler is one of the reasons that algebraic effects have gained increasing interest since their introduction. For readers familiar with monads, algebraic effects are restrictions on monads, which in some cases makes them a "weaker" abstraction, but in practice leads to a cleaner distinction between interfaces and implementations.

2 Multicore OCaml is specifically mentioned as an inspiration in the React docs, but languages like Eff or Koka -- despite being primarily research languages and not ready for the production spotlight -- were built specifically with effects in mind, which makes them a little easier to read for folks who don't yet know the language.

3 If you already know some OCaml, the syntax is largely identical.

4 A minor point: continue in Eff is actually just an identity function (provided in Eff's pervasives.eff). It was recommended by the Eff creators as a way to distinguish the continuation from a regular function, but of course you can always ignore it if you wish.

5 The Smalltalk community even has a web framework that uses continuations quite heavily, called Seaside.